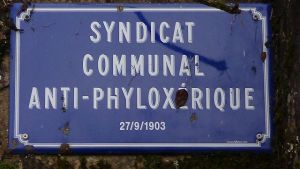

I came across this sign recently when I passed through the village of Villers-Marmery and it prompted me to do a little research into what happened in Champagne a century and more ago when phylloxera devasted the vineyards.

I came across this sign recently when I passed through the village of Villers-Marmery and it prompted me to do a little research into what happened in Champagne a century and more ago when phylloxera devasted the vineyards.

It’s been such a long time since the phylloxera catastrophe ( no that’s not too strong a word) laid waste the vineyards not just in France but across the whole of Europe that many people these days have never even heard the word let alone know what it means.

Phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae to give it its scientific name – it is also known as Phylloxéra vastatrix) is a small insect that attacks the roots of vines and eventually so weakens the plant that it dies.

It is believed that the bug somehow made its way across the Atlantic Ocean from the USA, possibly in a consignment of timber or some other wooden product. The insect was first notice in France in 1868 in the Languedoc and from there it spread across pretty much the entire country and into other countries. Its effects were disastrous; it destroyed huge swathes of vineyard and there was very little that the vignerons could do to stop it.

It is believed that the bug somehow made its way across the Atlantic Ocean from the USA, possibly in a consignment of timber or some other wooden product. The insect was first notice in France in 1868 in the Languedoc and from there it spread across pretty much the entire country and into other countries. Its effects were disastrous; it destroyed huge swathes of vineyard and there was very little that the vignerons could do to stop it.

Throughout the 1870s the Champagne vineyards were not affected and the champenois must have hoped that they would somehow escape the ravages of phylloxera, but in 1880 the first sighting of the bug was confirmed in the village of Chassins-Trélou in La Vallee de la Marne. From there it spread in 1882 to Le-Mesnil-sur-Oger in la Côte des Blancs and the following year it arrived in the vineyards of Epernay and eventually was spotted in La Montagne de Reims in 1904.

To give you some idea of the progress of the pest 14 hectares in Champagne were infected in 1897, by 1900 the count was 600 hectares; two years later it was 2,000 hectares, 5,000 in 1907 and by the time the First World War broke out 6,500 hectares of vineyards in Champagne had been destroyed. It’s worth pointing out also that in those days there were only 12,000 hectares of vines planted in the whole of Champagne, so over half the region’s vines were ruined.

It was in the 1890s that the vignerons organised themselves in associations to try to figure out way to combat the infestation and the sign in the picture at the top of the page presumably dates back to that period.

As early as 1879 even before phylloxera was established in Champagne a committee was set up to coordinate the fight against the pest. The majority of 26,000 registered vine growers, large and small, joined the committee but in a sad turn of events the committee was disbanded because the vine growers suspected the large négociants of exploiting the situation to buy up, at knock-down prices, the vineyards that had been affected by phylloxera. Perhaps the collapse of the committee was predictable and inevitable given the tenor of the times. There was huge suspicion of the négociants which culminated not many years later in the riots in Aÿ in 1911.

A series of cool years at the end of the 19th century slowed down the onward march of phylloxera and perhaps people thought they would get off lightly, but when the spread of the bug resumed the vignerons found that there was no way of stopping the insects. They tried flooding the vineyards to drown them; they tried burning the vineyards, but equally to no effect. The method most widely tried was to treat the vines with carbon disulphide by injecting it into the soil with giant copper syringes. Unfortunately this was a case of the treatment being almost as bad as, or worse than, the disease itself. Carbon disulphide is highly toxic and highly inflammable too and definitely not something you want to go spreading in the soil, moreover it didn’t work either.

The search for an effective treatment went on vigorously not least in the research centre set up by Raoul Chandon de Briailles in Fort Chabrol near Epernay. Eventually it was realised that American vines, Vitis riparia or Vitis rupestris ,were immune, or at least resistant, to the predations of phlloxera and that by grafting French vines Vitis vinifera onto the American root stocks one could retain the characteristics of the European vines on a plant that would not succumb to phylloxera.

The search for an effective treatment went on vigorously not least in the research centre set up by Raoul Chandon de Briailles in Fort Chabrol near Epernay. Eventually it was realised that American vines, Vitis riparia or Vitis rupestris ,were immune, or at least resistant, to the predations of phlloxera and that by grafting French vines Vitis vinifera onto the American root stocks one could retain the characteristics of the European vines on a plant that would not succumb to phylloxera.

This then was the news for which everyone had been waiting for 40 years and a programme of replanting was soon undertaken, although it was interrupted by the First World War. Little by little between 1900 and 1938 the native vines were dug up and replaced by grafts using the American stocks until, on the eve of the Second World War, there were just 95 hectares of native vines remaining.

One good thing did come out of this terrible episode. Until the arrival of phylloxera vines grew very much at random (en foule – ‘in a crowd’ - as the method is called). The new vines were planted in rows as we see them nowadays. This allowed animals and later tractors to work the vineyards which did a great deal to make the life of a vineyard worker a lot easier.

One good thing did come out of this terrible episode. Until the arrival of phylloxera vines grew very much at random (en foule – ‘in a crowd’ - as the method is called). The new vines were planted in rows as we see them nowadays. This allowed animals and later tractors to work the vineyards which did a great deal to make the life of a vineyard worker a lot easier.

They say that every cloud has a silver lining, but for the vignerons in Champagne it must has been hard to see it back in the early years of the 19th century.

Source material: article by Bruno Duteutre in Bulles et Millésimes http://www.champagne-news.com/1890-le-phylloxera-arrive-en-champagne/